In October 1914 the Ottoman Empire, at the behest of the Germans, had closed the Dardanelles to all allied shipping. Shortly after, the Turkish navy began attacking the Russian fleet at Odessa and Sevastopol, which led to a Russian declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire on 2 November. This was followed by the British declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire on 6 November.

Britain believed that the Ottoman Empire was weak, and that Turkey could easily be taken out of the war. Led by Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, a plan evolved in the late winter of 1914. The idea was to launch a naval campaign in the Dardanelles against Turkey. It was believed that success would be achieved quickly, and that once the straits had been secured by a joint British and French naval attack, a small force of troops would be able to march inland and take the Turkish capital, Constantinople. With the Ottoman Empire out of the war it was argued that Britain and her allies would then be able to attack Germany from the east. This would break the deadlock on the western front, weaken Germany and ultimately lead to an allied victory in the war.

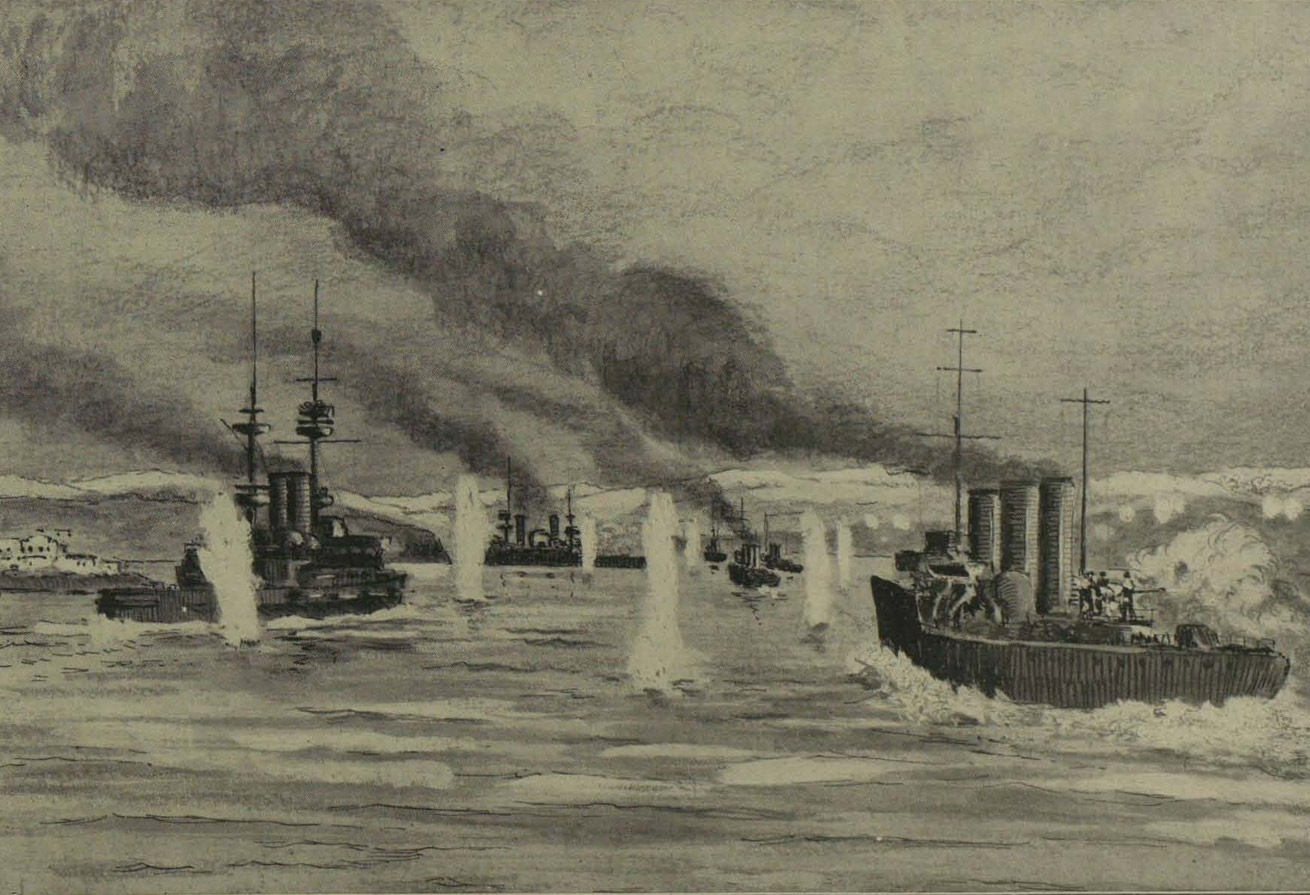

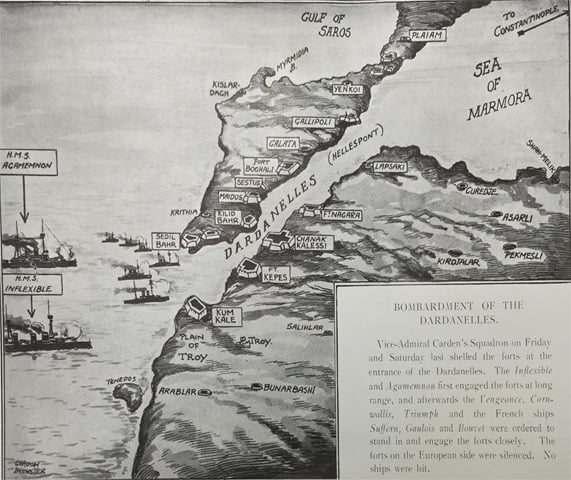

The plan to take the Dardanelles via a naval campaign was prepared in January 1915 by Vice Admiral S.H. Carden, and approved by the War Council on 13 February. The attacks would begin on 19 February.

An initial attack on the Dardanelles had taken place on 3 November 1914 to test Turkish resolve and weaken their defences. While limited, the attack was seen as a success. However, the time lag between the initial attack and the start of the campaign proper, over three months later, had given the Turks plenty of time to strengthen their defences and in particular to increase the number of mines they laid at sea.

On 19 February two destroyers, HMS Cornwallis and Vengeance were sent to mount an initial attack of the Gallipoli defences. The bombardment, which was fired from the ships some 12,000 yards from the coast, was met by the Turkish defenders, and the allies achieved no real success.

On 25 February, after a break in hostilities due to gales in the area, a renewed naval attack was made, but the allies were struggling to force their way through the extensive mine fields that the Turks had laid in the narrow waters of the peninsula. The following day the naval bombardment continued, and a small force of Royal Marines was landed on the coast to assist in the destruction of Turkish artillery positions.

In early March attempts to clear the mines continued, but strong ocean currents and Turkish artillery fire meant that progress was slow. On 4 March there was another beach landing at Kum Kale in order to disable Turkish artillery, but the attack was repulsed and 23 marines killed. Attempts at mine clearing continued in the first two weeks of March with some success, and it was decided to make a final, decisive attack on Turkish artillery positions and the mine network on 18 March.

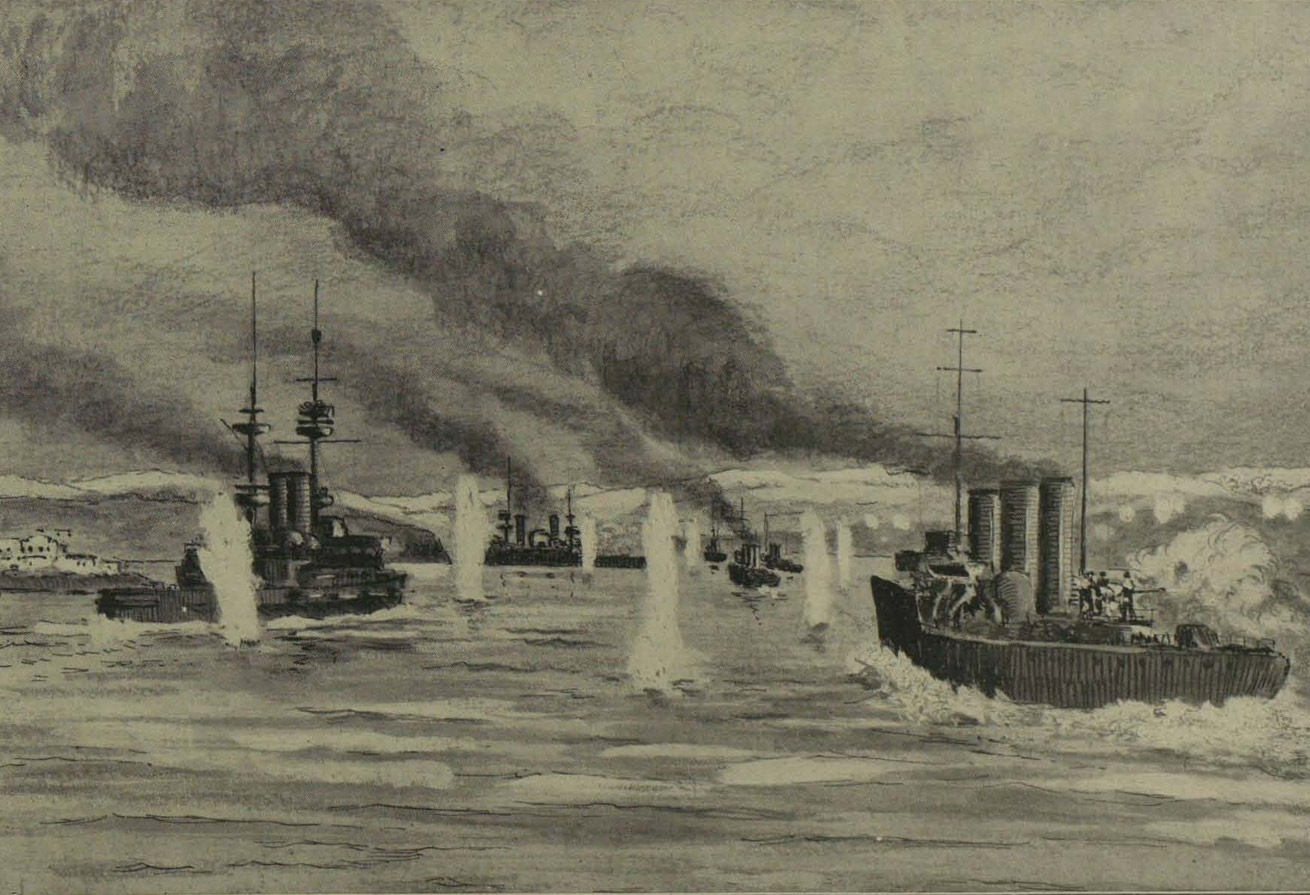

The attack was led by 14 British and four French ships, and the British ships opened fire on Turkish positions at 11 am. Within a few hours the Turkish positions had largely fallen silent, and it was believed that the attack was being successful. However, air reconnaissance had failed to spot a new line of mines that had been laid by the Turks on 8 March. At 1.54 pm the Bouvet struck a mine, and sank, killing all 639 men aboard. At 4 pm the Inflexible hit a mine, killing 30, and within two hours two further ships, the Irresistible and the Ocean had also struck mines. By the end of the day the allied navy had lost 3 battleships and 700 men.

Despite some pressure from Churchill and others to press on with the attacks after 18 March, the naval assault on the Dardanelles had failed. The reasons for the failure were multiple, but key factors include:

The failure to achieve a victory in the naval campaign was a serious setback for the allied forces. By 23 March, John de Robeck, commander of the Mediterranean fleet, was advising that the only way in which the Dardanelles would be taken was by a land attack. Unless the Turkish artillery positions overlooking the straits were taken and neutralised, de Robeck could not see how the mines could be successfully cleared.

The ultimate impact of the failed naval campaign was the decision to launch an assault on Gallipoli with troops that in turn would lead to eight months of stalemate and an eventual allied retreat. What was important about the naval failure was that it allowed the Turks to reinforce their defensive positions. The Turks had proved in March how strong their positions were, and that would be demonstrated again at the end of April when the land campaign began.