The terrible losses suffered by Irish soldiers at Gallipoli in 1915 left a tangible impact upon Irish society back home. Enid Starkie, a schoolgirl in Dublin during the war, described in her memoir the sense of loss among Dublin families following the news of Suvla Bay: 'Many of Walter’s friends were killed at Suvla Bay in 1915, when there was scarcely a family among us that had not lost someone. At school my intimate friends lost brothers and cousins whom I knew well.' Although her own brother, Walter, was rejected by the army as medically unfit, she wrote that the family felt ‘surrounded by sadness’. A similar sense of communal mourning is evident in Katharine Tynan’s memoir of the war years, published in 1919. Tynan, a well-known writer and poet in her time, powerfully conveys the devastation wrought by the Gallipoli campaign in Dublin in 1915: ‘Dublin was full of mourning, and in the faces one met there was a hard brightness of pain as though the people’s hearts burnt in the fire and were not consumed.' Tynan had two sons serving in the British Army during the war and although neither were at Gallipoli, the family had many friends who were killed in the campaign. On a visit from Mayo to Dublin in summer 1915, Tynan encountered two ‘new war-widows’ and another girl whose brother had been killed at Gallipoli. She powerfully evokes the despearate grief experienced by these young women: 'One got to know the look of the new widows - hard, bright eyes, burning for the relief of tears, a high feverish flush in the cheeks, hands that trembled, and occasionally an uncertain movement of the young head.'

How did Irish women cope with the grief at the loss of a loved one or their anxiety when their husband or son joined the army? Many became involved in activities on the home front to support the war effort as a means of distraction and of feeling as though they were contributing something to the war. Such activities included nursing wounded soldiers either on the home front or overseas, supporting Belgian refugees in Ireland, collecting sphagnum moss for surgical dressings, fundraising for specific regiments, and preparing parcels of food and clothing to send to Irish soldiers at the front or in the prisoner of war camps. Across the island of Ireland 5,688 women were enrolled with the joint committee of the British Red Cross and St John Ambulance Association. Red Cross volunteers performed a variety of tasks and served both on the home front in Ireland and Britain and also further afield, including close to the front in France, and in Malta and Egypt. One such Red Cross volunteer was Marie Martin, a Dublin Catholic, who served as a nurse in Malta and France in 1915 and 1916. Her younger brother Charlie had enlisted with the British Army on the outbreak of the war in 1914. Charlie Martin was injured at Suvla Bay but returned to active service before long. He was killed at Salonika in December 1915.

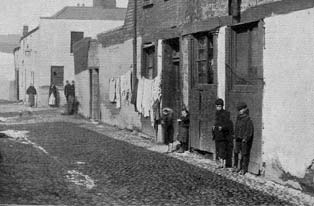

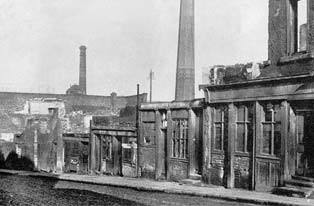

Some women found it too difficult to cope and turned to alcohol for solace. During 1915 there were very frequent reports in the press about soldiers’ wives engaging in excessive drinking. This was linked to the separation allowance, a weekly payment to soldiers’ dependents granted by the British War Office during the First World War. The separation allowance represented an increase in income for the families of unemployed men or casual labourers - among those most likely to enlist in urban areas. Many soldiers’ families in Dublin were living in tenements, indicating the very real economic motive for enlistment. The separation allowances became increasingly necessary as the war progressed due to the huge inflation in food prices. However in 1915 there were concerns about how soldiers’ wives were spending their allowances and allegations that the majority of such women were engaging in excessive drinking were common. It was alleged that they were going straight to the public houses after collecting their allowances from the post office. There were also reports of child neglect by these women and of violent brawls between the women and their neighbours. Such reports have proven to be greatly exaggerated and in fact the total number of women arrested for drink-related offences declined over the course of the war. The myth persisted however and those arrested for such offences met with little empathy for the anxiety and distress the women must have been suffering. One Cork woman arrested for public drunkenness in 1915 attributed the incident to her grief over hearing that her husband had been killed at the front. She was nevertheless convicted and threatened with a prison sentence. Her case was very typical of the treatment of working class soldiers’ wives at this time.

It has been estimated that approximately 35,000 Irish men (who enlisted from Ireland) were killed on active service in the war. In the majority of cases these men left bereft families behind. Thousands of Irish women lost husbands, sons or brothers, changing their lives forever. Marie Martin’s devastation at the loss of her brother Charlie is considered to be a significant motivating factor in her becoming a nun after the war’s end and her eventual establishment of the Medical Missionaries of Mary. The Gallipoli campaign also affected Irish attitudes to the Great War. Katharine Tynan described the news of the causalities suffered by the 10th Division at Suvla Bay as being the first moment of bitterness for many Irish people in relation to the war: ‘We felt that the lives had been thrown away and that their heroism had gone unrecognised.' The brutal reality of war had been brought home to the Irish people with the nightmarish horrors of the Gallipoli campaign and the casualties of Suvla Bay were particularly difficult to accept and process: ‘Suvla - the burning beach, and the poisoned wells, and the blazing scrub, does not bear thinking on.'