The Ottoman Empire, of which Turkey was the central part, was a vast and sprawling empire that had been at the height of its powers in the 17th century. At that time the empire stretched from the capital in Constantinople, west to the modern day Czech Republic, east as far as Iraq and across the northern coast of Africa. In the 19th century the Ottoman Empire went into decline, a process that was hastened by the costly Crimean War of 1853-6. In the decade and a half prior to World War One the Ottoman Empire shrunk still further. It lost Bosnia-Herzogovinia to Austria-Hungary in 1908, and Libya in a war against Italy (1911-12). In the Balkan War of 1912-13 the Ottoman Empire was reduced to the lands of modern Turkey, with some remaining territory in North Africa, after being defeated by the combined forces of Montenegro, Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria. During all these early twentieth century wars the death toll was enormous and hastened by ethnic attacks on the Armenian and Ottoman Muslim population.

By 1914 the Ottoman Empire consisted of some 28 million people. The majority were in Turkey (about 15 million) with the remainder stretched across Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan and parts of Iraq. At the time Turkey and its empire was headed by Mehmed V, the 35th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, who reigned from 1909. However, he had no real political power and was more significant as a state figurehead and leader of Islam. Political power led with the ‘Three Pashas’ who had taken power after a coup in January 1913. The three men who held power were Mehmed Talaat Pasha (Prime Minister), Ismail Enver Pasha (Minister of War) and Ahmed Djemal Pasha (Minister of the Navy). Under the men, Turkey effectively became a one party state led by their Committee of Union and Progress. The party ruthlessly stamped out any opposition, and put great store in modernising and increasing the size of the Turkish army. In August 1914 Turkey signed the Ottoman-German alliance which placed it alongside the Central Powers in the coming war. For Turkey the alliance meant that the Germans would provide military expertise and hardware to secure Turkish borders during the conflict.

The Ottoman Empire was often referred to as the sick man of Europe, and there was a widespread belief amongst the allies that the Empire was not strong enough to take part in the war. Indeed, Britain believed that the Ottoman Empire was so weak, and perhaps insignificant to the coming struggle, that it ruled out any alliance. The Sultan, Mehmed V, wanted the Ottoman Empire to stay out of the war, but the ruling CUP was open to approaches from the Germans that resulted in the alliance of August 1914. Initially, despite the alliance, the Ottoman Empire remained out of the war that had begun in August 1914. Initially the Ottoman Empire declared itself neutral, but announced in September 1914 that it would close its territorial waters to foreign naval traffic. This was particularly problematic for the Russians who depended on the Turkish Straits for access to its southern oceans. In October the Germans donated two warships to the Turks, but the crews staffing the ships remained German. On 29 October one of the ships attacked Odessa. The Russians took this as a declaration of war, despite the Turks explaining that the ship’s crew were German and had acted without instruction from Turkey. On 5 November the French and British declared war on Turkey in line with their pacts with the Russians.

Historians remain unclear as to why the Ottoman Empire went to war, and it seems that rather than acting on a predefined plan, events conspired to push Turkey to a counter-declaration against the allies. Ultimately the Ottoman Empire would enter the war alongside Germany and the other Central Powers on 11 November when Sultan Mehmed V declared war on France, Britain and Russia by proclaiming jihad against the allies. His move was ratified by the Turkish parliament three days later. One material benefit from declaring war against the allies was that the Ottoman Empire could stop paying its debts to France, Britain and Russia. In the autumn of 1914 Ottoman debts amounted to $716million. Of that total only 20% was owed to Germany, its new ally.

The Ottoman Empire fought in World War One on a number of fronts, and notably across Russian territory and in Persia and Palestine against the British. One of the bitterest and most contentious parts of the War was the Ottoman action against Armenia which was formalised by the Deportation Law of May 1915 that allowed for the forcible removal of Armenians in Anatolia. Although denied by modern Turkey, most historians argue that the attack on the Armenians by the Turks was effectively an act of genocide and, while estimates vary greatly, it is reckoned that in excess of 750,000 Armenians perished. Alongside these campaigns, the Turks also had to face allied forces on home soil after the decision was made to attack the Dardanelles and try and force a way through to Constantinople.

The initial naval attacks on the Dardanelles were repulsed by Turkish mines and inland artillery which led to the allied decision to attempt a landing at Gallipoli. In the month between the allied decision to make a landing the Turks were able to fortify their positions around the peninsula. The Gallipoli campaign, referred to as the Battle of Çanakkale in Turkey, was hugely significant for the defenders. While 250,000 men would end the campaign as casualties on the Turkish side, and thousands of them would die, the Battle of Çanakkale is held up as a great victory in the history of the Turkish nation.

The Ottoman forces at Gallipoli were under the command of the Çanakkale Fortified Zone. In the first few months of 1915, while the campaign was a naval one, the defenders were assisted by Vice Admiral von Usedom and 500 specialists in coastal defence provided by the German General Staff. The naval campaign, which was effectively ended on 18 March 1915, was a victory for the Turks. That day they fired 1,935 artillery rounds, and sank three allied ships. The defence had proved that a solely naval campaign would not allow the allies to get through the Dardanelles.

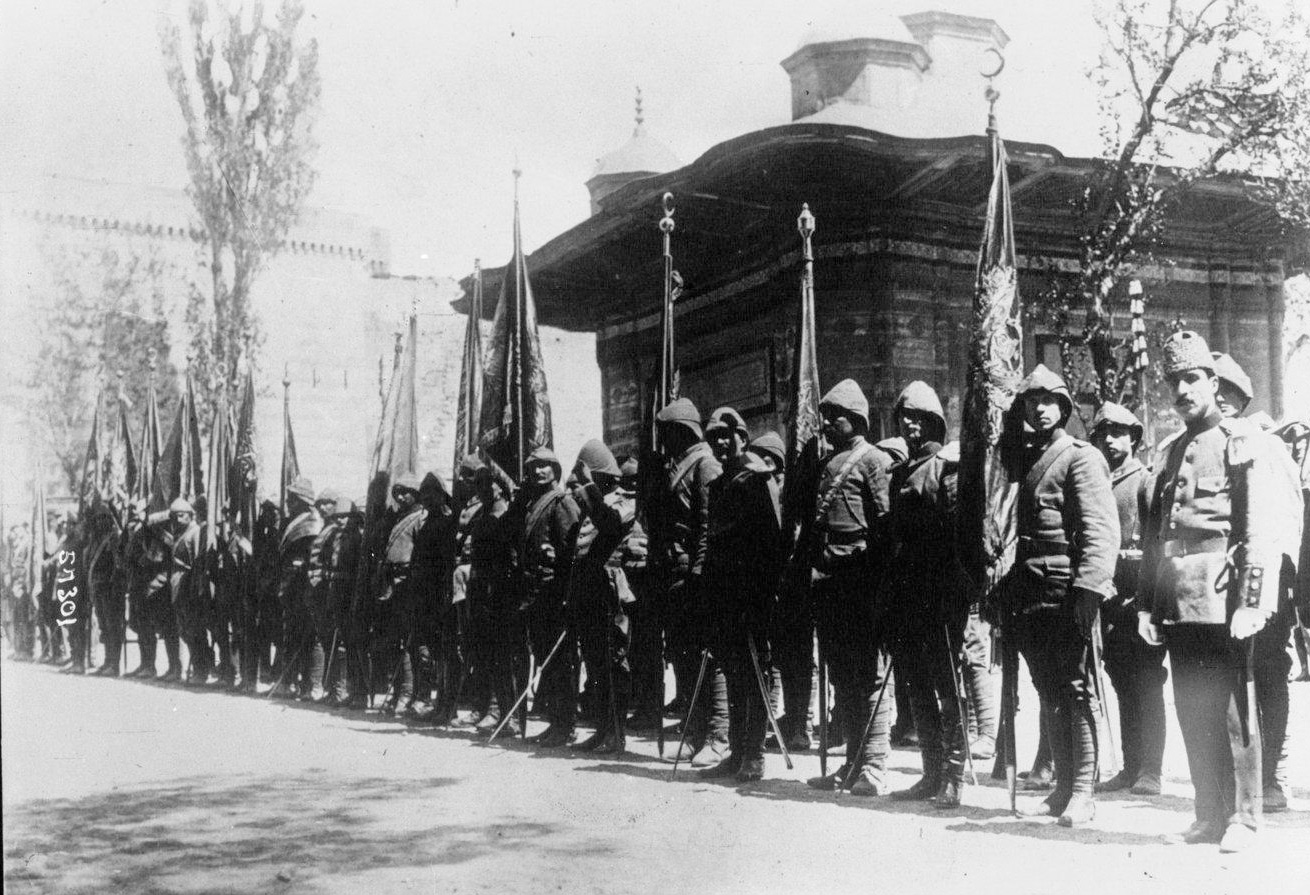

After the failure of the allied naval campaign the defending forces on the peninsula were strengthened. By the end of March a network of trenches had been built, and a force of 93,000 troops had been gathered in the region. They would fight under the overall control of the German, General Otto von Sanders.

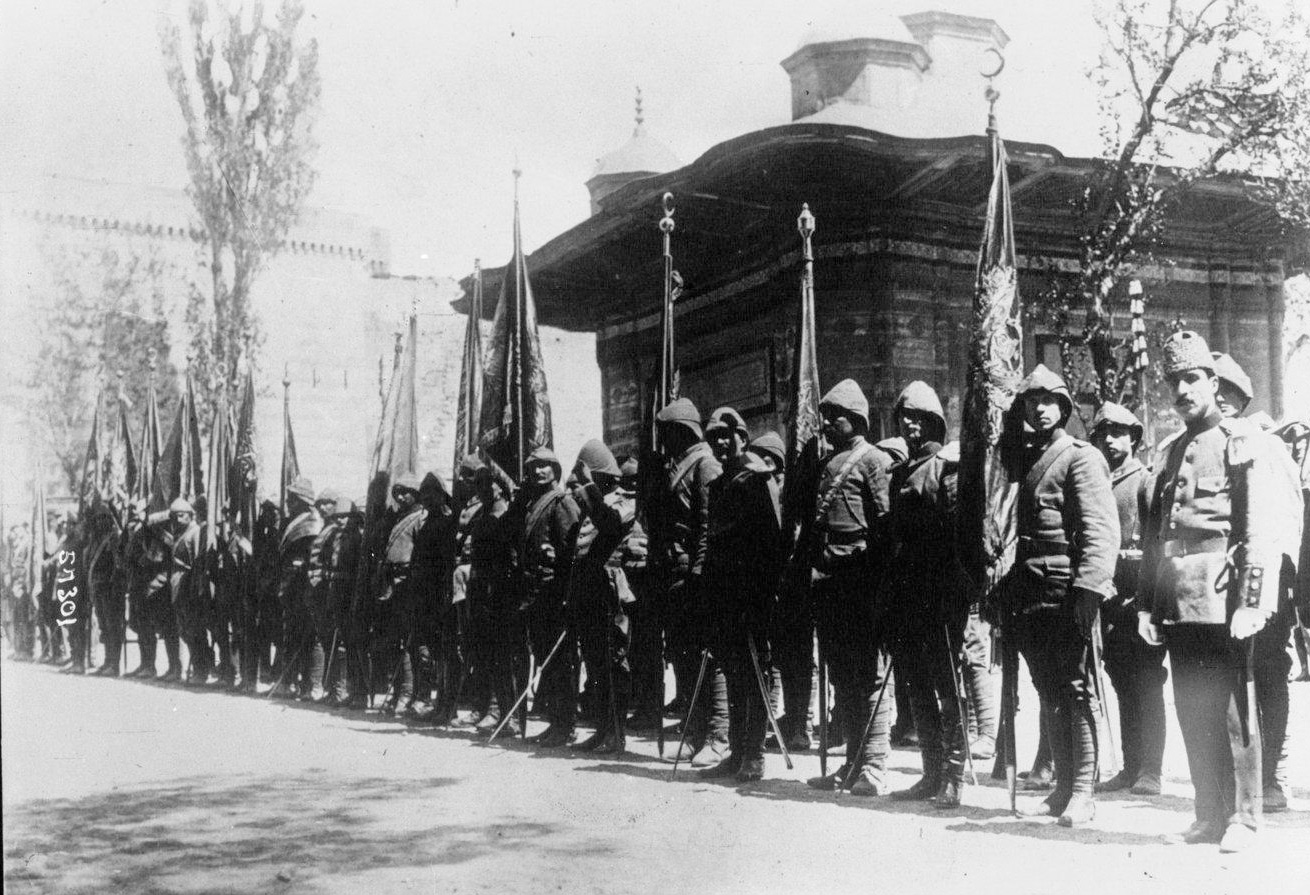

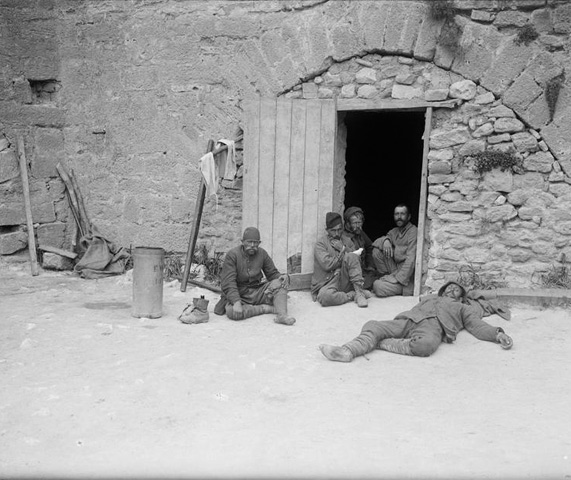

The allied landings at Gallipoli on 25 April had a key objective for that day: to reach Kilitbahir Plateau. As a result of the incredible defence put up by the 16,700 Turks who were on the peninsula that day – 6,000 of whom became casualties – the allied failed in their objective. Rather than taking the plateau the allies were pinned down on beaches and struggled to make their way in land. The Turks were not content to simply defend their homeland, but under the guidance of their local leader, Mustafa Kemal, they planned a large counter attack against the ANZACs at Ariburnu (ANZAC sector). The attack was not a complete success, but the ANZACs were forced back to the Nek and Hill 60. Further night attacks by the Turks took place on 1 May, and counter attacks by the allies days later. Despite the wrestling for control by both sides the front would become static with each side, barely metres away from each other, fixed in their trenches. The Turks were keen to mount another major attack and clear the enemy from its shores. On 19 May 42,000 Turks were lined up in the trenches and, at 3.30 am, sent over the top to attack the allied positions. Unfortunately the Turkish trenches were deep, and clogged with men. As each wave struggled out from their defensive positions they were cut down by allied machine guns. Within four hours of the attack beginning 3,855 Turkish soldiers had been killed and 5,967 wounded. It was because of the huge number of Turkish dead in the small area of no man’s land that the truce of 24 May was agreed so that the bodies could be buried.

By the end of July the fighting across the whole peninsula was a stalemate. By then, three months into the campaign, Turkish casualties amounted to 115,000 men, of whom 35,000 were dead. The allied landings at Suvla Bay on 6 August was another attempt to break the deadlock, but this was incomplete in its objectives and led once more to Turkish counter attacks. Here, as at the April landing sites, the fighting soon became static and the front lines barely moved. By the end of September there were 5,287 Turkish officers at Gallipoli and 255,700 troops. The lack of any movement in the lines of fighting would convince the allies to leave Gallipoli over December 1915 and January 1916. The Turks had won their victory and secured their homeland. The victory came at an appalling cost. By the end of the campaign it is estimated that Turkish casualties amounted to a quarter of a million men, and that 101,000 had been killed.

Although the Turks had been victorious at Gallipoli, they would lose the war. Across all fronts 771,000 men lost their lives in fighting, and it is estimated that as many as 4 million people in the Ottoman Empire were killed during the period of the war. The war was formally ended by the signing of the Armistice of Mudros on 30 0ctober 1918, which was followed by the allied occupation of Constantinople from November 1918 until March 1920. The Empire was broken up at the Versailles Peace Conference but strong nationalist feelings in Turkey led to the War of Independence (May 1919 – July 1923) which would lead to the creation of modern Turkey.

During the War of Independence Turkish forces were led by the former defender of Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal. The fighting was across a number of fronts, and pitted the Turks (who were assisted by the new government in Bolshevik Russia) against the British, French, Greeks, and Armenians. By 1922 the various forces began to look for ways to end the conflict, and in November 1922 all sides gathered at Lausanne to discuss peace terms. The resulting Treaty of Lausanne, signed in July 1923, recognised the Republic of Turkey as a sovereign state. On 23 October 1923, in the new capital Ankara, Mutafa Kemal was elected President and the Republic formally declared. In the summer of 1923 the last allied forces had left Turkey. The year previously, the Turkish Grand Assembly had voted to abolish the Sultanate, and on 17 November 1922, Mehmed VI, the last Sultan of the Ottoman Empire left Turkey aboard a British warship heading for exile in Malta.