The soldiers at Gallipoli became the concern of the medical services for two reasons: first, if they were injured in fighting; and second, if they became sick due to illnesses that were rampant on the peninsula such as dysentery. When a man was wounded he would be taken from the battlefield by colleagues or regimental stretcher bearers. In a time of attack, reinforcements had the right of way in trenches, and often the injured would have to wait for hours before being removed from the front line.

Just behind the front line was the Regimental Aid Post. Here men would be initially treated, wounds would be dressed and drugs administered as necessary. They would also be identified and ticketed so that the later chains in the medical process knew who the man was, the nature of his wounds and the treatment to date. Once the wounded soldier had been assessed he would be transported to a Casualty Clearing Station, most of which were situated on the beaches. Here men would be fed and watered and, if their condition was life threatening, they would be operated on. For most men, especially during major offensives, the Casualty Clearing Station would mean a long wait until they could be evacuated to a hospital ship.

The sheer number of wounded at Gallipoli, and the problems of the allied forces having no extensive rear lines meant that dealing with and then evacuating the wounded and sick was a logistical nightmare. The wounded had to wait for available lighters (small ships) that would transfer them from the beaches to hospital ships waiting out at sea.

In addition to those men who were wounded in fighting, many men also reported sick. They would report each morning at the daily medical parade and be assessed by the Regimental Medical Officer. The scale of sickness was incredible, and only twice during the campaign (early May and mid-August) did the numbers of men being evacuated from Gallipoli due to wounds sustained in fighting outstrip the numbers being taken off with some form of illness. While dysentery was the most common ailment, men were also evacuated due to sunstroke, synovitis, impetigo, nerves, hernia, blood poisoning, pleurisy, colic, phlebitis and tonsilitis. Sickness combined with fighting injuries meant that scores, and sometimes hundreds of men had to be moved off the peninsula each day.

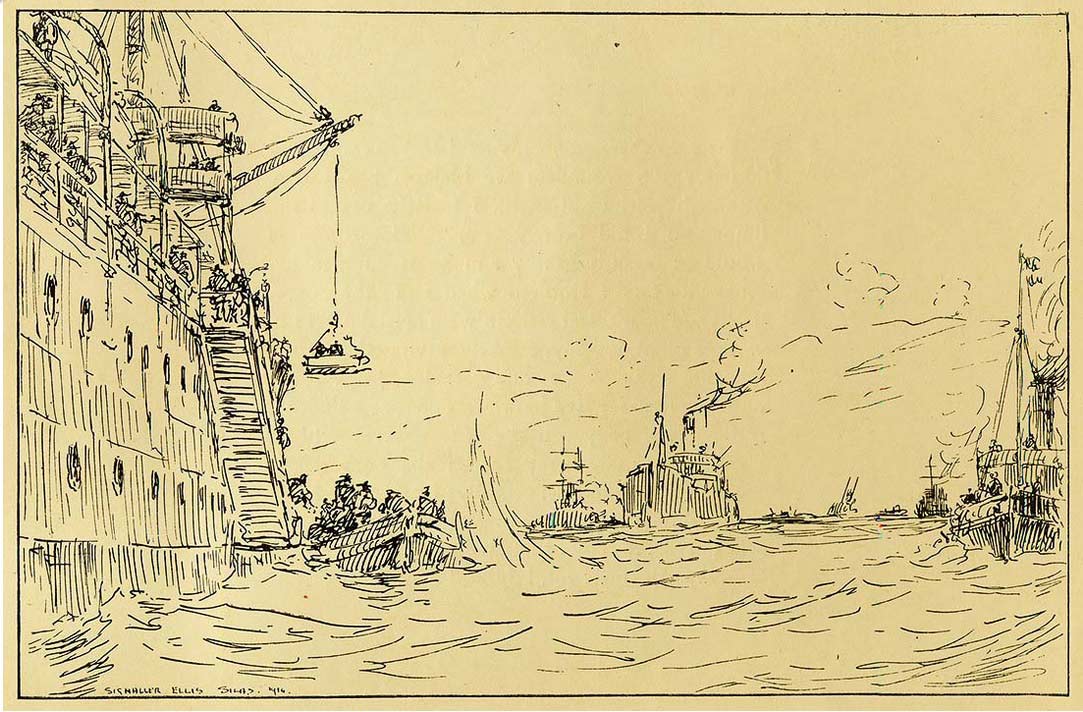

[Image: Ellis Silas' drawings – Crusading at Anzac]

Once they had been assessed at the Casualty Clearing Station on the beach, men would either walk or be carried by stretcher to one of the temporary piers that had been constructed at Gallipoli. They would then be loaded onto the lighters and taken to the hospital ship. Although short, the journey from pier to ship was hazardous. The sea was often stormy, especially in the winter months, and the lighters were a constant target for Turkish bullets. Signaller, Ellis Silas, recalled the process of moving from beach to hospital ship: ‘I reach the clearing station - it presents a scene of well-ordered confusion; everywhere on the narrow beach are numbers of wounded awaiting their removal to the hospital ship. This cannot be carried out until well after sundown, for the enemy is sending a continuous rain of shells in this direction. Ere our transfer to the boats we each have a label pinned on us stating the nature of our wound. Many are gasping out their lives before they can be transferred to the boats. We are put into the boats and are towed away to the hospital ships - we are towed from ship to ship; always the same reply, ‘Full up’ - eventually we manage to get aboard one. The cot cases were hoisted on board by derricks. The sea is fairly smooth, which is fortunate - a sailor tells me during the choppy seas of the last few days the wounded suffered terribly when being put aboard the hospital ship. Even right out here an occasional shell comes buzzing through the air and drops close alongside - it would be really rough luck to get hit so far away from the firing line after having been in such thick scrimmages.’

The hospital ships were protected by the Geneva Convention, and always marked with red crosses to distinguish them from standard naval vessels. Many of the hospital ships used at Gallipoli were passenger liners that had been requisitioned by the War Office and converted for the purpose of transporting the wounded. Nurses, who were never used on the ground in Gallipoli, staffed the ships and cared for the sick and wounded while they were in transit. It was common that four doctors, six nurses and a number of orderlies would be on each ship administering to the needs of approximately 400 men. On board there were operating theatres, and many of the seriously wounded would be operated on as the ship journeyed towards it destination. More generally, men were also cleaned and their dressings changed as necessary.

A total of 56 hospital ships were used during the Gallipoli campaign, and their sole function was to move the sick and wounded away from the peninsula and transport them to hospital bases where they could be fully treated. For those whose ailments were less serious, and recovery was expected in three weeks, ships transported them to Lemnos. More serious cases were transported to Egypt, Malta or back to England. Given that the hospital ships were often very crowded, and men were suffering from wounds or sickness, the journey was challenging and long. It took four hours sailing to get to Lemnos, three and a half days to travel to Alexandria in Egypt and six days to get to Malta.

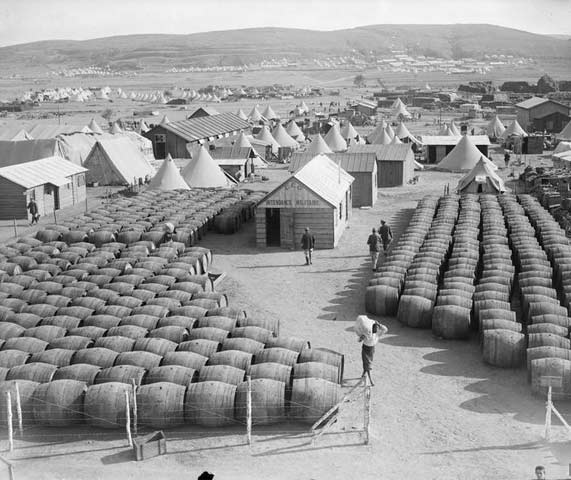

The hospital at Lemnos had 18,000 beds available from May 1915, and was ideally placed for transporting large numbers of sick and wounded due to the proximity of the deep water harbour at Mudros. Lemnos was home to Australian, British, Canadian and Indian hospital and casualty units. During the course of the campaign it treated both the sick and those who had been wounded. The more seriously wounded, or those who needed longer periods of convalescence were moved on from Lemnos after initial treatment. As with Gallipoli itself, the hospital at Lemnos had problems with getting an adequate water supply, and as such maintaining hygiene was a constant problem.

Egypt was the main allied hospital base, and had 36,000 beds available by the close of the campaign. During the course of the Gallipoli campaign some 104,000 patients passed through the Egyptian hospitals. The scale of the medical challenge was evident four days after the campaign began when the first wounded arrived at Alexandria. In total, on 29 April alone, 2,489 casualties were admitted to the hospital there. The need for large spaces suitable to accommodate the wounded and sick meant that a range of buildings were requisitioned for use as hospitals including an amusement park, skating rink and a number of hotels.

It was envisaged at the start of the campaign that Malta would have 3,000 beds available to treat the Gallipoli wounded, but that number grew to 20,040. During the course of the campaign 57,900 men were treated in Malta. The first wounded arrived on 4 May 1915 and totalled 600 soldiers who were followed by a further 1,140 forty eight hours later. Initially there were only 14 nurses in Malta, but given the numbers of patients the size of the medical teams were expanded rapidly in Malta and elsewhere from early May.

Across the period of the campaign, and in those places where the allies constructed temporary hospitals to treat everything from wounds through to dysentery and venereal diseases, 85 separate medical and convalescent facilities were built.