The first Irish who arrived in Australia in the 18th and early 19th centuries were convicts, often political prisoners, who were sent there for a period of incarceration, after which they were to make their homes on the vast continent. They were soon followed by tens of thousands of Irish labourers and other workers who sensed an opportunity in starting afresh in a new land. Many of these 19th century Irish who went to Australia paid for their own journeys, while many others took advantage of assisted passage schemes. These allowed the British government, and the state authorities in Australia, to populate the continent quickly. By 1891 there were 228,000 Irish born people living in Australia, and they formed one of the largest ethnic groups settled there. Towards the end of the 19th century the numbers of Irish immigrants to Australia began to slow, and by the time of the 1901 census the number of Irish born had reduced to 184,035. That said, it is regularly estimated that by the first decade of the 20th century that those of Irish heritage comprised approximately a quarter of the Australian population (the number of Irish born in 1911 made up 3.1% of the total population).

The Irish were largely successful in Australia. Although negative connotations were attached to them, as in the United States, and fears expressed over their Catholicism, drinking habits and levels of violence, the Irish rose to prominent positions in society at speed. The Irish were successful in various business enterprises, at the heart of the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s and particularly prominent in the police and other judicial services. With no conscription in Australia, Irish settlers were free to join the armed services (or not) as they wished, and there was a steady influx into the forces over the years. In World War One the numbers would increase dramatically.

As a loyal part of the British Empire it was no great surprise that the political leadership of Australia instantly supported the British declaration of war. To protect Australia and deal with German forces in the wider Pacific region the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force was formed, and first saw service in September 1914. The bulk of Australian men who volunteered for service joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) that was specifically raised for service overseas. By the end of 1914, 52,561 Australian men had volunteered to join the armed services. In all likelihood the men of the AIF would have expected to be going to fight on the western front. However, after the first AIF troops left Australia in November 1914, they were initially sent to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal. While there, the decision was made in London to attack the Turks at Gallipoli. The AIF would see its first fighting not, as they imagined in France or Belgium, but rather in Gallipoli from the end of April 1915. Here they would be grouped with New Zealanders, and form the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs).

During the Gallipoli campaign some 26,000 Australians would be injured, and of these 8,141 were killed. The sacrifices of these men, accusations of poor British leadership and stories of Australian heroism all combined to create the idea that the modern Australian nation was forged at Gallipoli. ANZAC Day, the 25 April, is annually observed as a commemoration to those who served and fell at Gallipoli.

After the evacuation of Gallipoli, Australian troops would see further service in Egypt, Palestine and across the western front. At the end of the war there were 167,000 Australians in active service. Given the logistical challenge of repatriating such a high number, the majority of Australians did not return home from war service until 1919. In all over 420,000 Australian men served in World War One. Of these 60,000 would never return home and are buried in Commonwealth war cemeteries across all theatres of the war.

It has been estimated that some 6,600 Irish-born men and women served in the Australian Imperial Force during World War One. From the research carried out by Jeff Kildea we know that the Irish-born comprised 1.58% of enlistments in the Australian army in the war. While at first hand this figure seems low, Kildea has shown that the Irish population in Australia by 1914 was an aging one, and that only 1.8% of the Irish male population was of military service age. What is also significant about those Irish-born who joined up in Australia is that they were often recent arrivals. Around two-thirds of those Irish men who would enlist in the AIF had arrived in the country after 1909 when a reinvigorated assisted emigration scheme was at its peak.

The Irish ANZACs were drawn from across the island of Ireland, with the largest numbers being drawn from Antrim, Dublin, Cork, Down, Tipperary and Derry. In the context of Gallipoli it is important to remember that many of the Irish ANZACs unearthed by Kildea would have volunteered to serve later than 1914, and therefore would have served in other parts of the world and not Turkey. There was a huge spike in recruitment in Australia, and among Irish Australians during the summer of 1915 and again in 1916, and obviously none of these men would have ever served in Gallipoli. Before the end of 1914, 854 Irish ANZACs had enlisted and were likely to have seen service in Gallipoli, so in effect it is approximately 12% of the total number of Irish ANZACs who are strictly relevant to the campaign. Those Irish ANZACs who enlisted after the Gallipoli campaign were particularly active in service in Europe and the Middle East.

In many ways the stories of the Irish ANZACs at Gallipoli mirror those of other allied troops. Conditions were harsh, the fighting was bitter and the number of men wounded, sick and killed was high. The key point in all this was that Irish men who had settled in Australia, and then decided to fight in the war, contributed to the great story of their adopted nation. As Kildea concluded: ‘...in the First World War the Australian Irish played their part in building that most enduring edifice of Australian national identity, the ANZAC tradition.'

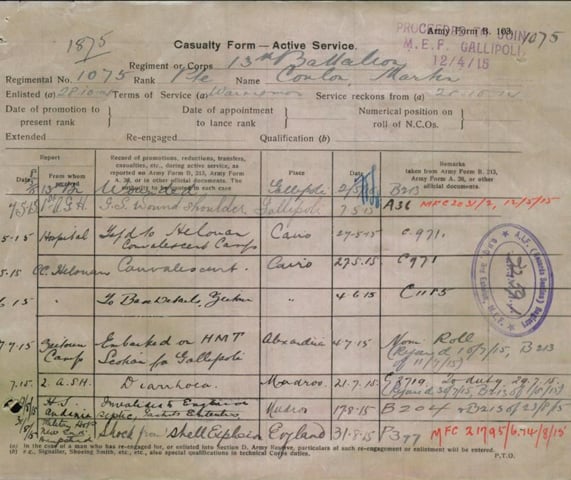

Beyond the ultimate legacies of the ANZAC tradition and the part that Gallipoli played in forging modern Australia, what of those Irish men that found themselves in Gallipoli fighting in an Australian uniform? Some, such as Martin Conlon, originally from Carrick-on-Shannon, enlisted in Liverpool, New South Wales, just shy of his 27th birthday, and would end his campaign invalided out of service. He had landed at Gallipoli in April 1915, and was first recorded as wounded on 2 May. On 7 May he was injured again, this time suffering a gunshot wound. He was sent to convalesce in Cairo, before being returned to Gallipoli on 7 July. He would subsequently return to hospital in late July suffering from diarrhoea. In August he was caught near an exploding shell and sent to England to recover. Once in hospital in England he was diagnosed with ‘shock from shell explosion’ and would be eventually discharged from the army and return to Australia in early 1916.

Other men paid the ultimate price for the service. Joseph McIlwaine was born in Belfast, and enlisted in the army at Leongatha in Victoria where he had been working as a labourer. McIlwaine was 23 years old, a Presbyterian and had moved to Australia with his family. McIlwaine entered the fighting at Gallipoli on 8 May 1915 and was there only five days before he received a gunshot wound to the head. He was removed from the peninsula so that he could be hospitalised in Alexandria, but died of his wounds on board the hospital ship Royal George on 13 May. He was buried on 15 May at the Chatby Cemetery in Alexandria. In his will he left all his possessions to his sister, Kathleen, who was living in Koonwarra, Victoria. She was also sent a box from Alexandria that contained his disc, copy of his bible and a note book, which she would receive nearly a year later on 27 March 1916. On 10 September 1922 his father would receive a Victory Medal on behalf of his deceased son.

A common experience for the Irish ANZACs who went to Gallipoli was survival followed by a posting to the western front. However, four years of military service usually came at a cost, and few men returned home unchanged by their experience. David O’Dwyer, who had been born in Wexford, was a 34 year old unmarried fireman when he enlisted. He was living in Melbourne at the time, and that’s where he signed up and was sent to serve in the 1st Division Signal Company of the AIF. He sailed from Australia on 22 December 1915, and would land in Gallipoli on 19 May 1915. In August he left the front and was sent to hospital suffering from influenza, but was able to rejoin his company a month later. O’Dwyer would finally leave Gallipoli on 29 December 1915 and was then admitted to hospital in Cairo suffering from enteric disease where he was listed as ‘dangerously ill’. Unlike many men who contracted the disease he survived, but clearly his experience had damaged him. On 22 March 1916 he was charged with being absent from the force without leave. By the end of April he was considered well enough to return to his unit which, by this time was in training camp at Tel al Kabir in Egypt. Clearly his return to service was too soon, and within ten days he was returned to hospital with a diagnosis of ‘debility’. He spent time in hospital in Alexandria, before being sent to England for further hospitalisation in the London General Hospital where his diagnosis was once more enteric disease. Four months later, in September 1916, he was transferred to a dedicated enteric hospital but again, on 30 September, was charged with being absent without leave. O’Dwyer would spend the winter of 1916 and the spring of 1917 between hospital and his unit. Every time he was classified as fit for service, he would relapse and find himself back in hospital. In April 1917 he was arrested and charged on two occasions for being absent. In May that year he was finally judged well enough to be sent overseas again, and was posted to his unit and stationed at Abbeville on the western front. O’Dwyer’s ways didn’t change once he was in France, and he was arrested twice by the Military Police for again being absent without leave. On 27 August he was admitted to the First Australian Field Ambulance, and while there was no explanation as to his injuries, he was treated for deafness which suggests he found himself in the proximity of an exploding shell. By 26 September 1917, O’Dwyer was back in hospital in England where he would spend the remainder of the war dividing his time between various hospitals (including treatment for venereal disease), his unit and further periods of absence without leave. He was finally sent home from England on 17 March 1919, and was discharged from service on 17 May 1919 when he was back in Melbourne. All told, O’Dwyer had been in the army for four and a half years, and was clearly affected throughout his service by the after effects of the enteric disease he had contracted in Gallipoli. One wonders how many men had experiences similar to O’Dwyer. Men who joined up with enthusiasm in 1914 only to experience the fighting and disease of Gallipoli, and then serve the remainder of the war as shadows of their former selves.

The Irish ANZAC database is fully searchable and free to use. It is available online.

More details about the work of Jeff Kildea and his writings on the Irish ANZACs can be found at: jeffkildea.com and in his book ANZACs and Ireland published in 2007 by Cork University Press.