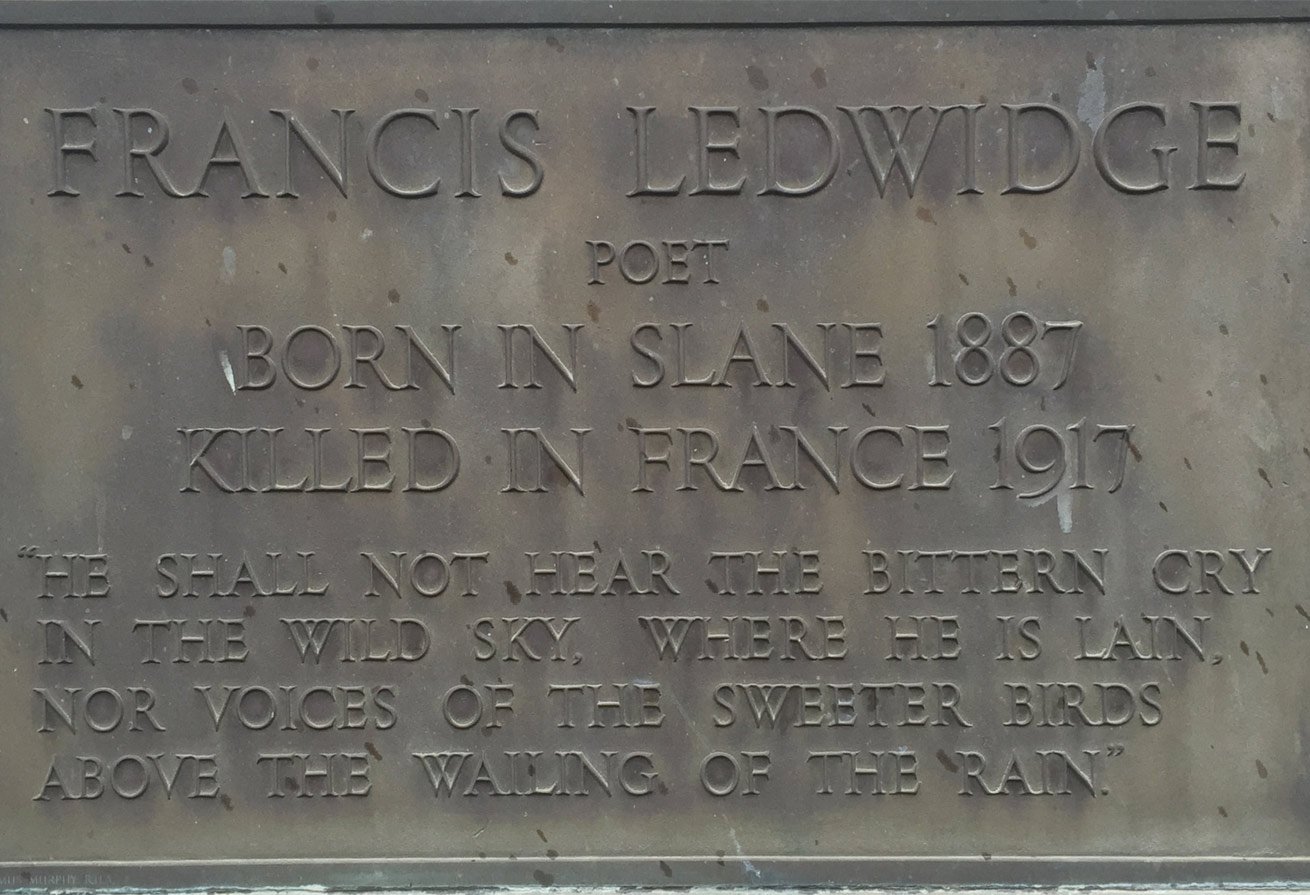

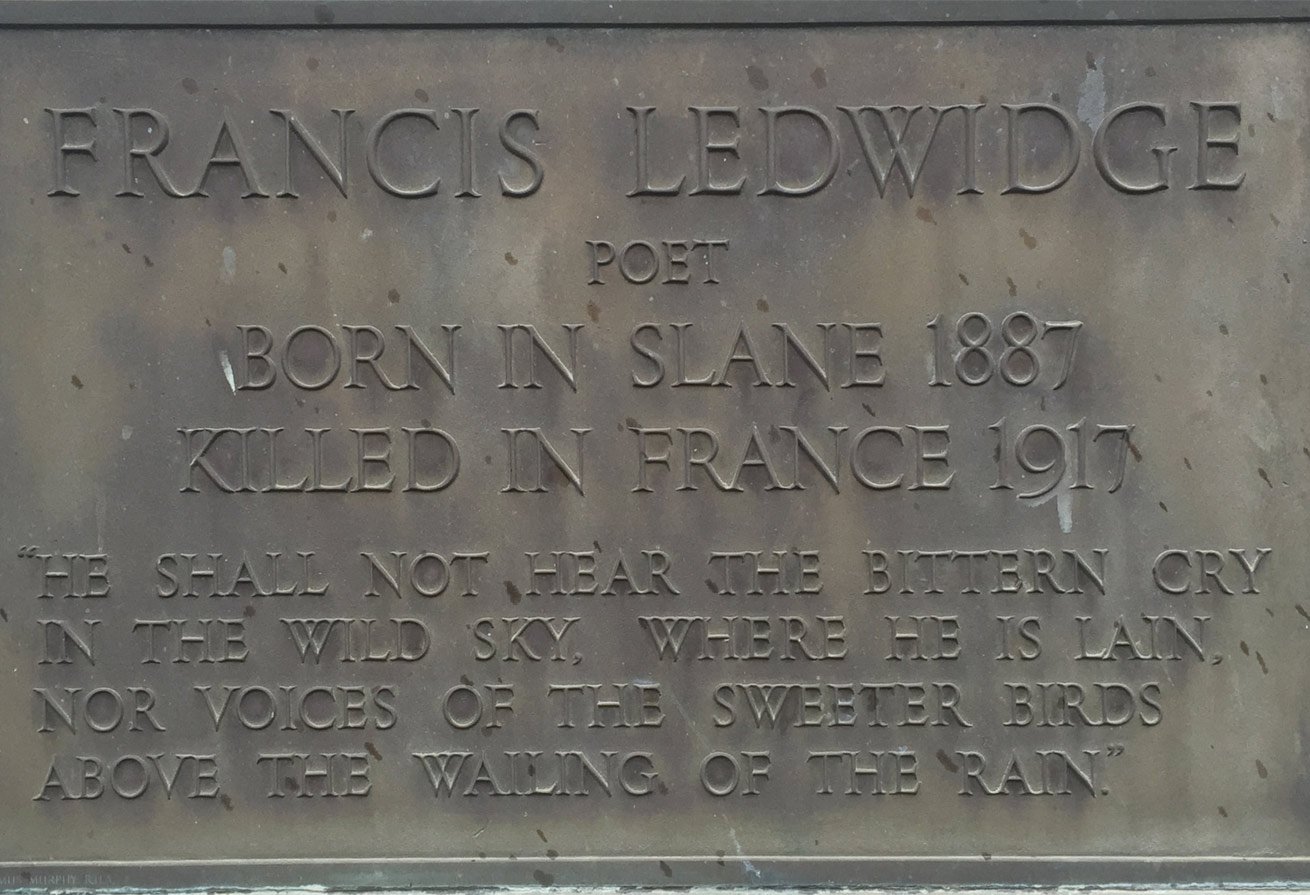

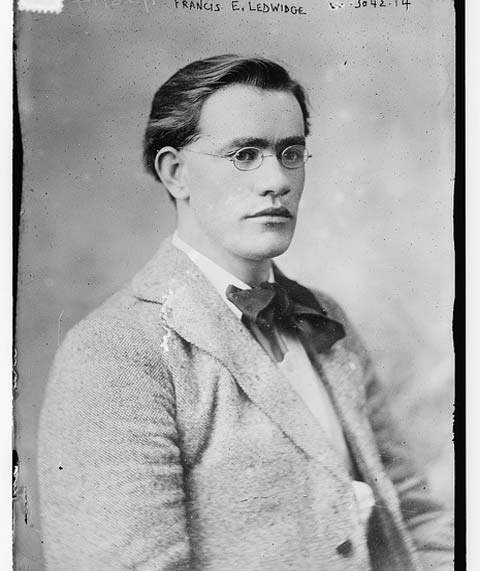

Francis Ledwidge was born on 19 August 1887 at Janesville, Slane, Co. Meath. He was the eighth of nine children, and his father, Patrick, was a farm labourer. Ledwidge attended Slane national school but due to the family’s straightened financial circumstances he had to leave school at 13 and take work as a farmer’s boy. By 1907 he was working as a road mender, and three years later was appointed as supervisor of roads for the county. He was always interested in the conditions of the labouring classes, and in 1906 was a founder of the Slane branch of the Meath Labour Union. Just prior to the outbreak of World War One he was the temporary secretary of the union.

When not working, Ledwidge immersed himself in the history of the Boyne Valley, read widely and began writing poetry. Encouraged by a local curate, Fr Smith, Ledwidge began contributing his poetry to the Drogheda Independent. Ledwidge was later befriended by Lord Dunsany who would become an invaluable patron. Dunsany’s lecture to the National Literary Society in October 1912, which foregrounded Ledwidge’s pastoral and historical poetry, created interest in the young poet. He was admired by many of the leading figures of the literary revival of the period. Prior to the outbreak of war Ledwidge had established himself as an important Irish poet and writer.

Ledwidge was a keen supporter of the Home Rule movement. In the autumn of 1913, when the prospects of a successful implementation of Home Rule was threatened by unionist opposition, Ledwidge took action. Along with his brother Joseph he was one of the founders of the Slane branch of the Irish Volunteers. He regularly took part in Volunteer meetings, and was also active in the drills and marches of his local branch.

Following the outbreak of war in August 1914 the Volunteers split. The majority would follow Redmond in his support of the war effort as the National Volunteers, while a minority would remain in the Irish Volunteers led by Eoin MacNeill. Ledwidge was initially sceptical of Redmond’s support for the war, and he remained outside of the National Volunteers and away from the army recruiting offices.

By 1914 Ledwidge was the recipient of a weekly allowance from Dunsany, and could have remained at home to write during the war. However, Meath was a county that embraced the war, and it appears that Ledwidge was eventually swept along with the prevailing pro-war sentiment. On 24 October he joined Lord Dunsany’s regiment, the 5th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 10th (Irish) Division) at Navan, and was sent to Richmond Barracks in Dublin.

Ledwidge, despite his initial reticence to join the war effort, would later justify his decision: ‘I joined the British army because England stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation, and I would not have had it said that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions.' Ledwidge took the rank of lance-corporal, and was sent to Basingstoke to complete his training. In early 1915 he was able to return to Slane for a brief visit before joining his battalion and sailing to Gallipoli.

Ledwidge landed at Gallipoli in July 1915. By the time that Ledwidge arrived on the peninsula the initial landing zones had been secured, but a stalemate had set in with neither side advancing. He took part in the major August offensive, a joint allied attack on Suvla Bay. Ledwidge landed on the morning of 7 August, but as with the April offensive, the allied forces were attacked by the defending Turks and struggled to get off the landing beaches. The offensive was a failure, and rather than advancing inland to secure their objectives, Ledwidge and the 5th Battalion remained trapped not far from the beach. Ledwidge would later refer to his arrival on the beach as ‘a great day which he would not have missed’.

Given the stalemate and the growing sense that the Dardanelles campaign would have to be abandoned, Ledwidge and the 10th (Irish) Division were removed from Gallipoli in October 1915. Ledwidge found himself in Serbia where his regiment suffered from a harsh winter and many men fell ill from the effects of frostbite. The fighting in the region was hard, and on 9 December the 10th (Irish) Division came under heavy attack from a much larger Bulgarian force and suffered 1,500 casualties. Ledwidge survived, but damaged his back during the retreat to Salonika, and was subsequently hospitalised in Cairo and later in Manchester.

Ledwidge was in hospital in Manchester when he heard the news of the Easter Rising. He was badly affected by the execution of his friend Thomas MacDonagh. His poem dedicated to his friend, 'Lament for Thomas MacDonagh' is critically applauded as one of his best works. On leaving hospital Ledwidge was allowed to go home on leave. His family found him a changed man, and he appeared completely disillusioned with the allied war effort. In conversation with his brother Frank, his change of heart was revealed when he said that ‘if someone was to tell me now that the Germans were coming over the back wall, I wouldn’t lift a finger to stop them'.

His experience of warfare and in his response to the Easter Rising, Ledwidge was clearly radicalised. He had no stomach for his return to the front at the end of his leave. He failed to report for duty on the correct date, and was subsequently arrested for appearing drunk in uniform in May 1916. At the ensuing court martial hearing he was found guilty of overstaying his leave and for insubordinate talk. As punishment he lost his lance corporal’s stripe and was returned to service.

Ledwidge returned to the front in France in the second half of 1916, and saw action at the Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917. He was then ordered north to Belgium in preparation for the 3rd Battle of Ypres. The offensive began on 31 July 1917, but Ledwidge was kept in reserve behind the lines and put to work laying roads.

Working with fellow members of his battalion near the village of Boezinghe, Ledwidge was far in reverse of the front line. Unfortunately during the afternoon of 31 July, a long range German shell exploded next to where Ledwidge was working. He was killed instantly, along with five of his fellow Inniskillings. The battalion chaplain, Fr Devas, who had given Holy Communion to Ledwidge that morning, wrote in his diary, ‘Ledwidge killed, blown to bits’.

Ledwidge was buried close to where he died at Carrefour de Rose, and was eventually reinterred at the Artillery Wood Military Cemetery.

Ledwidge received a copy of his first published collection of poems, Song of the Fields (1915), while he was serving on the Serbian border. His next collection, Songs of peace (1917) was published posthumously, and included his war time poems as well as that which he dedicated to MacDonagh. His patron, Lord Dunsany edited two further collections for publication, Last Songs (1918) and Complete Poems (1924). Most relevant here is Ledwidge’s Dardanelles poem, 'The Irish in Gallipoli'.

In 1980 Seamus Heaney wrote 'In Memorium Francis Ledwidge', a poem that acknowledged the complex personal choices that were made by Irishmen during the World War One and the changing political landscape following the Rising in 1916. With the increase in interest in Irish participation in the War, Ledwidge was memorialised at the Island of Ireland Peace Park in Messines. His former home in Janeville, Slane, has been operating as the Francis Ledwidge museum since 1982.

Where Aegean cliffs with bristling menace front

The treacherous splendour of that isley sea,

Lighted by Troy’s last shadow; where the first

Hero kept watch and the last Mystery

Shook with dark thunder. Hark! The battle brunt!

A nation speaks, old Silences are burst.

‘Tis not for lust of glory, no new throne

This thunder and this lightning of our power

Wakens up frantic echoes, not for these

Our Cross with England’s mingle, to be blown

At Mammon’s threshold. We but war when war

Serves Liberty and Keeps a world at peace.

Who said that such an emprise could be vain?

Were they not one with Christ, who fought and died?

Let Ireland weep: but not for sorrow, weep

That by her sons a land is sanctified,

For Christ arisen, and angels once again

Come back, like exile birds, and watch their sleep.

Follow the stories of the Irishmen who fell at Gallipoli from a century ago via their personal stories, ephemera, archive material, census details, military archives and diaries.